|

FRANK L. BORCHARDT 1938-2007

A CELEBRATION OF HIS

Doris Duke Center

September 20, 2007

PRELUDE

Ave Maria

Ingeborg Walther, piano

WELCOME

Ann Marie Rasmussen

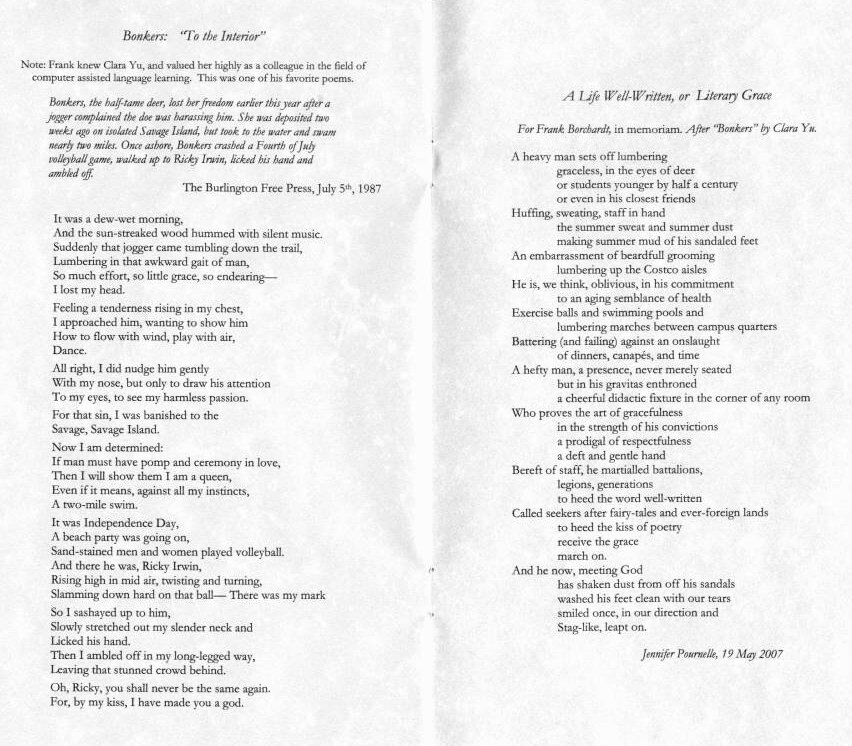

On behalf of the Department of Germanic Languages and Literature at Duke University, I welcome you to this memorial for Frank Borchardt. We have gathered here, family, relatives, friends, neighbors, colleagues, and students, to share memories of Frank, and to honor his legacy. Frank was on the faculty at Duke University for thirty-five years. He was a passionate and early champion of Educational Technology. He was also a champion of early modern German culture, and he ceaselessly advocated for the cultivation and preservation of pre-modern studies both within the field of German studies and, more pragmatically, at Duke University. Frank loved the German language, German literature and German poetry, and he loved teaching. Whether in first year German courses, or in his large lecture course, German Fairy Tales, or in the seminar on Goethe's Faust which he completed only weeks before his death, Frank touched the lives of countless students in profound ways. Many of them are here with us today. We are many here today, and many more students, colleagues, and friends of Frank's, unable to attend, have sent word that they with us here in spirit. Thank you for coming. It is good to see you here. And as Frank would say in closing, 'Be sweet.' RECOLLECTIONS

James Rolleston Many of you will have stories about Frank, both serious and amusing. We were colleagues for 32 years, so my plan is to give a quick overview of his professional achievements, particularly the innovations of his chairmanship. But it’s through a personal story that I reached this. Lunching with Frank just a few years ago, I asked him what his retirement thoughts might be and whether we should coordinate such plans for the Department’s benefit. “Retire from what?” he answered. When I looked blank he added: “The Department is my family.” I still didn’t really get it, as I don’t think that way. But during his last years I think I began to understand. Everything in German culture was alive in Frank’s mind, particularly Goethe of course, but also all the byways of older literature, and the vital need, in our time, to reanimate the traditions of Bildung, self-development, which earlier scholars had taken for granted. And the Department had to be the agency of this reanimation: the Department is where words and ideas about things German are exchanged on a daily basis. It doesn’t happen anywhere else. One reason Frank always took colleagues’ ideas seriously, even when he disagreed, was that the discussion itself was what counted, however casual it might appear; we all remember, when we ended a conversation to go teach, that Frank would say: “Be brilliant!” One smiled inwardly, of course. But I think he really meant something. The teaching process, for better or worse, was the final outcome, for that day of course, of the continuous process of Bildung. So he hoped we would do better, not worse, and nourish the life of the German Studies organism, of which we are a part. I know that makes Frank sound almost like a rabbinical scholar, holding sacred texts close. But that side of him was so productive because, like a radical artist, he lived simultaneously in the future. We see that in two of his great accomplishments: luring his mentor, Harold Jantz, to Duke in the early 1980’s, together with his legendary book and manuscript collection—this has been a huge advance for German Studies at Duke. Early Modern conferences attract the best scholars in part because they want to explore the Jantz Collection. And then, in the late 1980’s, he pioneered the new idea of computer assisted language instruction. Of course, there was a pre-pioneer, Frank’s colleague, Leland Phelps, who will be speaking today and whose innovation Frank praises in the book he co-edited about Leland’s career. But in CALICO, Frank’s computer project, he found his key moment of Bildung. As always, deep past and immediate future nourished each other. When Frank presented possible uses of computer techniques to graduate students, he grounded them in Lessing’s aesthetic categories from the 18th century. Frank was hugely spontaneous. I know I’m making him sound more self-conscious than he was; that may be inevitable when reflecting on such a productive life. So I’ll close with a musical story. Many years ago, when Leopold Stokowski’s recording of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony was released on LP, Frank and I bought it almost at the same time. Since we agreed it was the greatest, we spent a couple of hours listening to it together at his house. And then this April, when the graduate students were presenting their projects, one of them, who hopes to integrate Mahler into a German Studies dissertation, played a recording of a lovely Mahler song. After a brief silence at the end, Frank said: “Is there anything more beautiful?” That’s how I’ll always think of him: teaching beauty and meaning by intensely living them both.

Professor Emeritus and former Chair, Germanic Languages and Literature, Duke University Frank’s death was much more for me than the loss of a dear friend and colleague. He was part of our family. Ruth and our three daughters were immediately drawn to him by his outgoing personality, hearty laughter, and his rich store of tales and anecdotes. We included him in our family activities, to which he always added a very special aura. When the girls grew up and left home, they never forgot their ebullient, bearded friend. No visits involving children and grandchildren were complete without Frank. Thirty-some years ago my colleague, Henry Stern, asked if we could invite his friend, Frank Borchardt, to give a lecture at Duke. I agreed and made the necessary arrangements. When he arrived I was introduced to a well-dressed, vibrant, beardless young man who proceeded to captivate the department with his personality and an outstanding lecture on Bert Brecht. Everyone agreed that he should be recommended for an opening in the department. The Administration accepted this recommendation, and in the fall of 1972 Frank became a member of the Duke German Department. He was not only a congenial and cooperative colleague, but also a superb teacher, totally dedicated to his students. His influence on them often extended beyond the undergraduate years. Many of them have stayed in touch with Frank over the years; indeed, several of them have made the trip to be here today from as far away as Germany and France! Following my retirement in the fall of 1986, Frank and I often met for lunch and spent an hour or two chatting and eating (obviously one of his favorite activities). During the last few years my wife Ruth joined us and we began to notice the onset of major health problems. He, however, refused to let them interfere with his various activities. Even when the problems became serious, he refused to slow down, though the need for a cane and chemo-therapy made life somewhat more complicated. The crisis came in the summer of 2008. His doctors told him not to plan on teaching in the fall. (He had been scheduled to teach two of his favorite courses, Rilke and Kafka in the fall of 2006 and Faust in the spring of 2007). Frank was adamant -- he insisted on teaching in the fall of what he knew would be his last year in the classroom. Reluctantly, the doctors told him he could try, but they were not optimistic. Needless to say, Frank not only started but finished the semester. Then the doctors insisted he could not possibly teach the Faust course in the spring. However, in spite of his worsening condition, Frank persisted. By sheer will power he forced his body to obey him and, to the amazement of his doctors, finished the semester. Ruth and I had lunch with Frank just before he turned in his final grades. He asked me to take him to the hospital the next morning because he had to go in for some tests. He told me to go home; he would call me when he was finished. There was no call --- he never returned to his home.

Professor of German, University of North Carolina at Asheville When I went to Northwestern to begin graduate work friends of mine who knew Frank told me to look him up—he was a clean-shaven junior Professor at the time. I waited over a year and when I finally did introduce myself he growled “You’re late, where have you been?” I was then ordered to report to his house the next evening. I did, we listened to Anton Webern, drank German Mosels, and my informal, nearly life-long and indeed life-altering education in German began—to say nothing of a cherished, and I believe remarkable, friendship. For 4 decades Frank and I exchanged hundreds of letters, thousands of e-mails, we traveled together, and visited here and in Asheville. We also kept several phone companies profitable. For about a year somewhere in that period I didn’t hear from him—my version is that he was sulking, but I don’t recall why. When we were much younger, had plenty of pocket money, and letters from universities guaranteeing life-long employment we went traveling. Frank on holiday was a force of Nature, tireless, exuberant, irrepressible. Even Paris, supposedly smug and indifferent, capitulated. His Prussian-tinged French charmed waitresses, he traded jokes and Gaulois with cabbies. There was no defense against Frank’s good humor and laughter, posturing was futile. In the US we met regularly at professional meetings, whether in New York, Chicago, or San Francisco. Often I drove to Durham to pick him up or he came to Asheville for a visit before SAMLA. As in everything, Frank the houseguest was extravagantly generous and utterly idiosyncratic. On one occasion his house gift was a welcome, and anticipated, case of Franconian wines; on a later visit, however, he presented us with a pound of silver— to buy bread on the black market, he explained, after the Left had finished wrecking the economy. A teddy bear for the children was only slightly smaller than a bear For my sons, now grown, Frank is a storied figure, a legend. Prudently I have never divulged to them his theories on childrearing. Asheville’s quirks and eccentricities appealed to Frank, but he insisted that mountain air smelled funny, the spectacular sunsets over Beaver Lake he labeled purest kitsch. He always maintained Nature was best experienced through a picture window. In 2000 we met for what was to be our last stay together in Europe. In Berlin. We saw Lessing’s ‘Nathan’, took the S-Bahn out to Sachsenhausen where Frank’s father had been imprisoned, and rode the #100 bus the length of its route. He talked about George Grosz and Marlene Dietrich and told of his days in early 60’s Berlin—the parties, meeting Horst Buchholtz, the Winter darkness. We toured the Nikolai Quarter in former East Berlin and strolled down Unter den Linden, stopping for a moment at the statue of Freiherr vom Stein to pay our respects. It felt very much like home. But what we both sensed, though left unsaid, was that there would be no future trips. That was hard to accept. Conversations with Frank were always exhilarating, never brief, covered every topic imaginable, and a few unimaginable. For a time he was holding forth on 5th century heresies; then rhetorical and literary devices. I now notice and nod at parasiopesis and anaphora, and I am fully prepared for encounters with Pelagians and recalcitrant Nestorians. Curiosities aside, Frank was always mentor and inspiration: his stunning insights into Kleist’s work, for example, moved me to return to the Novellas, reread, and discover what I had long missed. Over the years he gave me 2 reproductions of a 1546 Luther Bible (for some reason he thought one wouldn’t be enough), but more importantly he helped me appreciate Luther’s life and work. His recitations of long passages from Faust prompted me to similar, if less heroic, efforts. In the end all conversations came around to students: Doug’s career in Europe, Joe’s whereabouts, whether Janine was still at Kentucky. Chicago in 1966, Durham in 2007—he hadn’t changed. His affection for his students endured. How fitting that Baird Straughn, dear friend and former student, was with Frank during those final weeks. In recent years we had been meeting in Durham at Biscuitville, Guglhupf, and of course Bullock’s: pilgrimage site, storehouse of memories. Meals with Frank were magical… and uproarious: ideas, anecdotes, and the occasional errant hushpuppy caromed wildly about, while his beard told the tale of meals past. When I think of Frank, a daily occurrence, no exceptions, we’re at a table where the sweet tea refills keep coming, the accents around us are thick with the NC Piedmont, and an indefinable aura of well-being envelopes it all. Telephone calls became much more frequent a year or so ago: he had minutes left over, he claimed (and sometimes adding that he had tried calling several interesting people but they weren’t home). He was in discomfort or pain but that wasn’t why he called—he called to talk. He could live with pain but not without conversation. And what he assured me, repeatedly, was that he was in spite of everything happy. After all, he had Boyle’s Goethe biography, lunches with Lee and Ruth , the Baragonas, holidays feasts at the Stapletons’, exercising with Martha Blake-Adams, former students stopping by, his ongoing 38-year battle with Pegge Abrams—he knew what really mattered . And while most of us measure our lives in months and years, for Frank it was semesters. What elation then when his oncologist gave him another semester—another chance to teach Faust. He did and then departed gracefully and courageously. But what he never lost was his indomitable sense of irony, his enviable ability to recognize, yet laugh at life’s minor inconsistencies and major absurdities. That irony remained intact, unbroken to the very end of his life. A small consolation perhaps, but a consolation nevertheless. I’d like to read you a short poem by the German writer/poet Theodor Storm. It’s titled ‘Oktoberlied’’, song of October. I chose this because Frank and I visited Storm’s home in Husum on the North Sea and spent a sunny afternoon there at the harbor, trying to imitate Low German songs we knew from old Lale Anderson records. Ms. Anderson would have been mortified. We both liked ‘Oktoberlied’ and when I read it to him at the Hillsborough hospice and came to the line ‘mein wackrer Freund’—my sturdy friend—he lifted and turned his head slowly, half smiled and then fell back into semi-consciousness. Later Baird Straughn, who had been in the room, confirmed what I thought/hoped/prayed but perhaps just imagined I had seen.

President, CompEd, Inc. Brother of Frank Borchardt

The parents of Frank Borchardt were immigrants from Germany --- more specifically, refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. Our father Hermann arrived in New York in June 1937 somewhat damaged from 10 months in Nazi concentration camps. Efforts by friends in the US resulted in his release on the condition that he leave Germany immediately. My mother, older sister and I followed a few months later.

The parents of Frank Borchardt were immigrants from Germany --- more specifically, refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. Our father Hermann arrived in New York in June 1937 somewhat damaged from 10 months in Nazi concentration camps. Efforts by friends in the US resulted in his release on the condition that he leave Germany immediately. My mother, older sister and I followed a few months later.

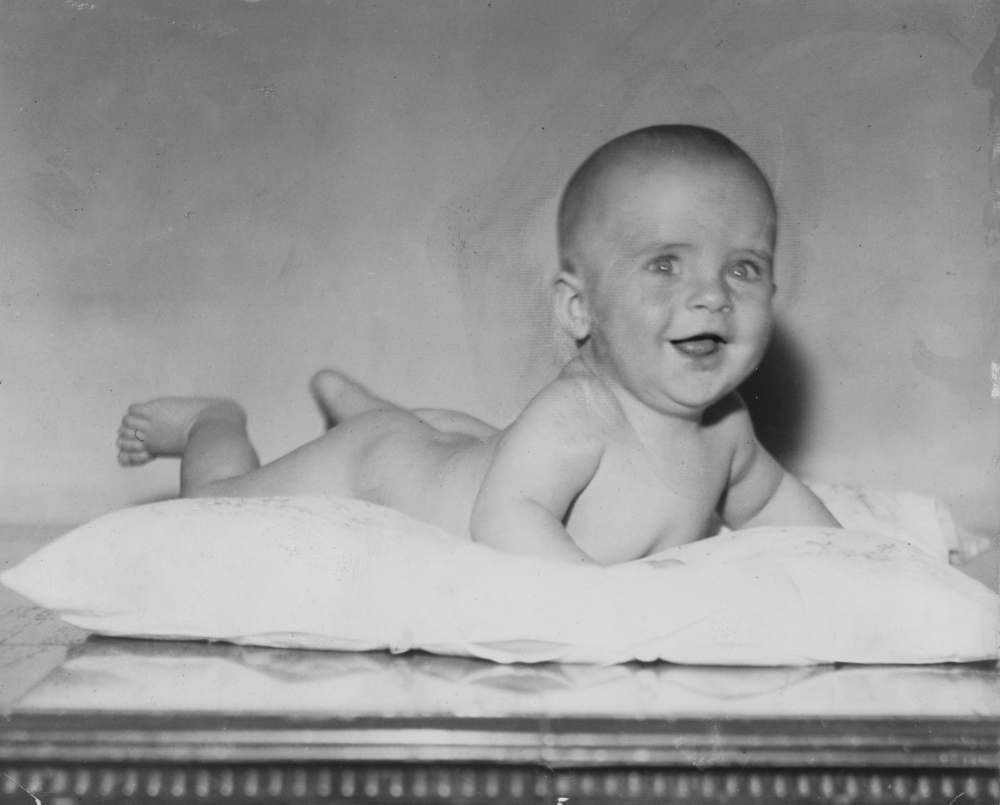

The reunion in this country was a joyful one – as evidenced by the arrival not long thereafter of a new Borchardt, Franklin Lewis.

NAME

CREATIVE -- RENAMES

CONSERVATISM The reason had to do with his leaving Germany with Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, going to France where he could not find employment, then accepting a position in Russia, teaching German. Experiencing the realties of the so-called “workers paradise”, seeing how badly people were treated, how poorly the system worked caused the reversal which we both inherited.

OUTSPOKEN If Frank was ever outspoken when his self interest would have been better served by silence --- I don’t know that this ever happened, but if it did --- it wasn’t Franks fault. It was the Borchardt genes! Blame Hermann!

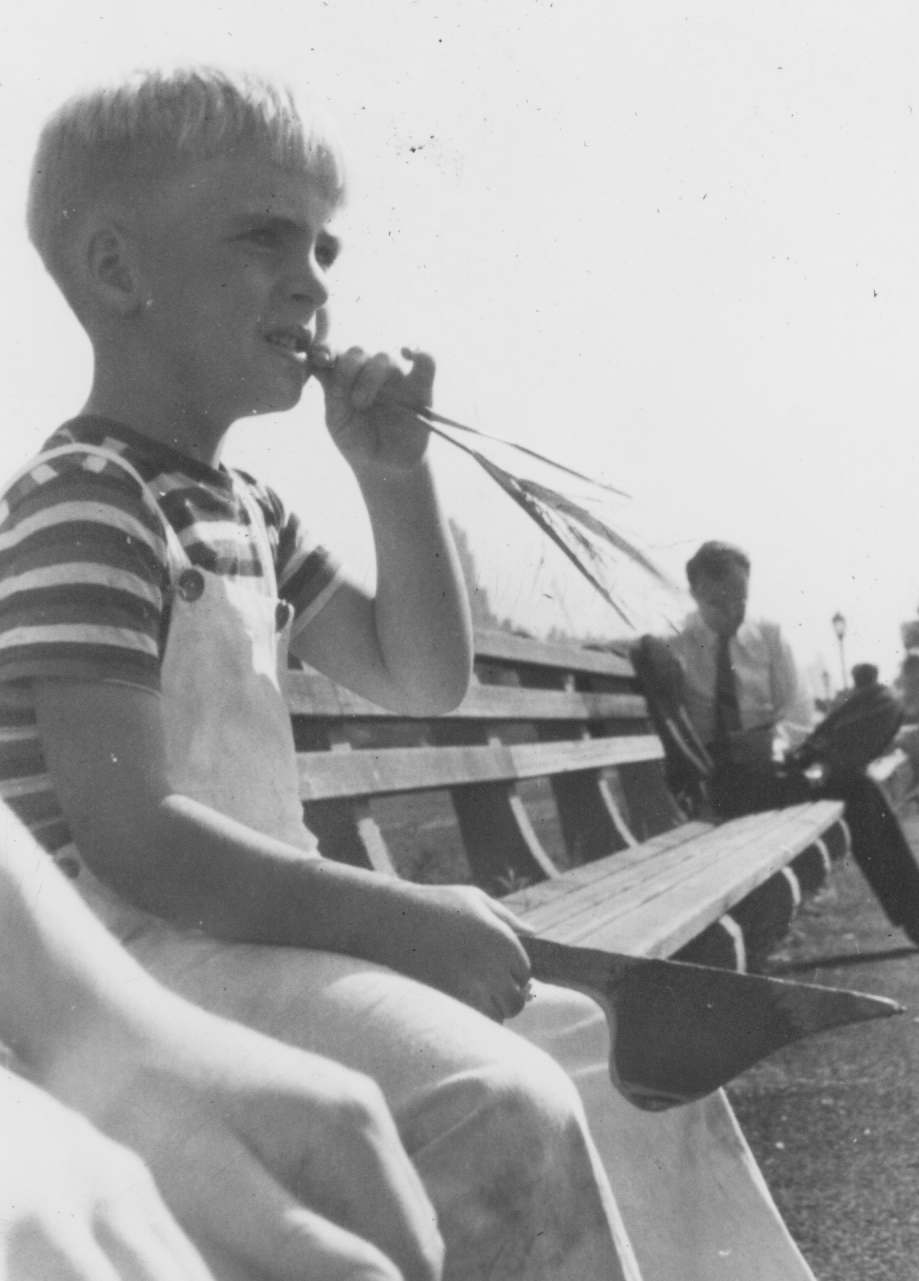

EARLY ENVIRONMENT -- POVERTY However, not too far away was the Hudson River and Riverside Park where we would go for an outing. At left is Frank at age 2; at right at age 5.

MORNINGSIDE DRIVE

EARLY SCHOOLING

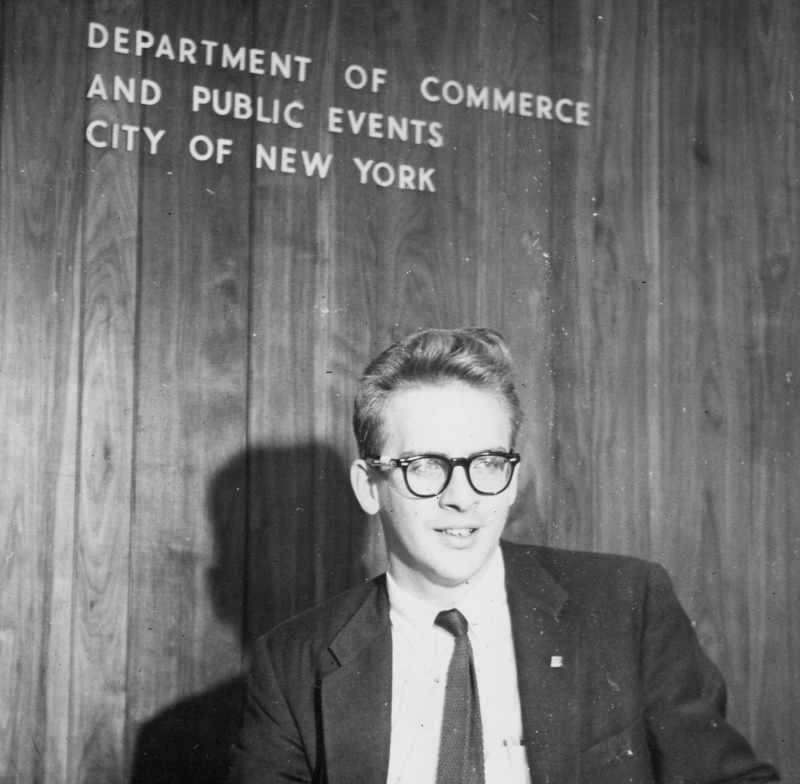

He and Mimi came to visit me in Wisconsin where I was a graduate student and where I introduced him to the wonders of perch fishing on Lake Mendota --- and he was good at that too. He held a summer job as advisor at the Times Square information center where he could express his opinions on what was best on and off Broadway.

But the extra curricular activity with the greatest impact on Frank and his future career was drama. He became enamored with it and was an active participant throughout high school and college. He had leading roles in Macbeth, The Tempest, King Lear, Tiger at the Gate, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and many more --- and was superb at it – as evidenced by the outstanding reviews that he received. Frank as King Lear is above.

THE TEACHER-ACTOR (ACTOR-TEACHER)

FRANK’S PASSING

THE BIRD So there was a valid message and what appeared to be a persistent messenger. Did this involve Frank’s spirit? Probably not. The timing of the birds arrival was most likely just coincidence and its behavior this was just a dumb bird that couldn’t seem to learn that you can’t fly through glass even after months of trying. But maybe not. There is no way of knowing. Maybe Frank’s spirit was involved. If so, he is likely to be here amongst us right now. Frank loved life, he loved a party and he wouldn’t miss this party for the world. If he is here he would be reminding me to thank the organizers, his students, his colleagues and guests. I want to thank in behalf of myself and our family, all participants, particularly Professor Walther--- for honoring my brother in this fashion. Thank you.

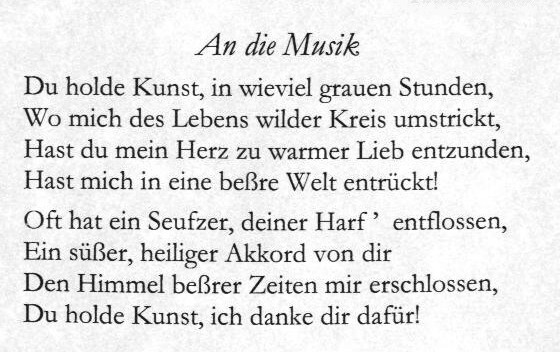

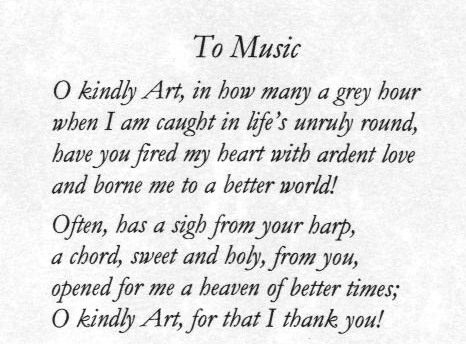

An die Musik

Susan Dunn, soprano

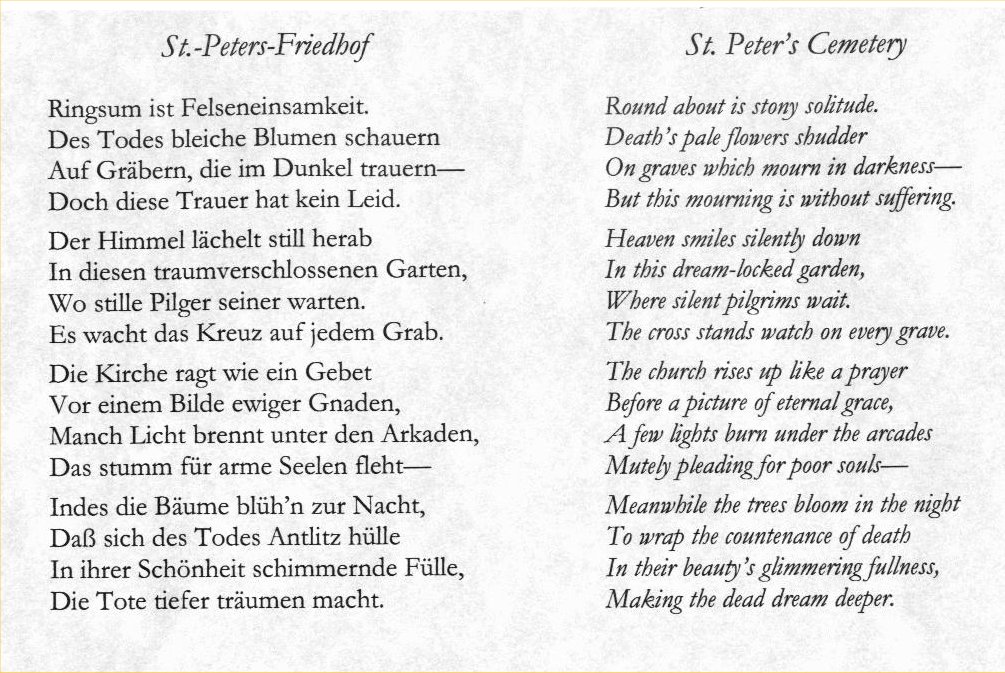

St. Peters-Friedhof

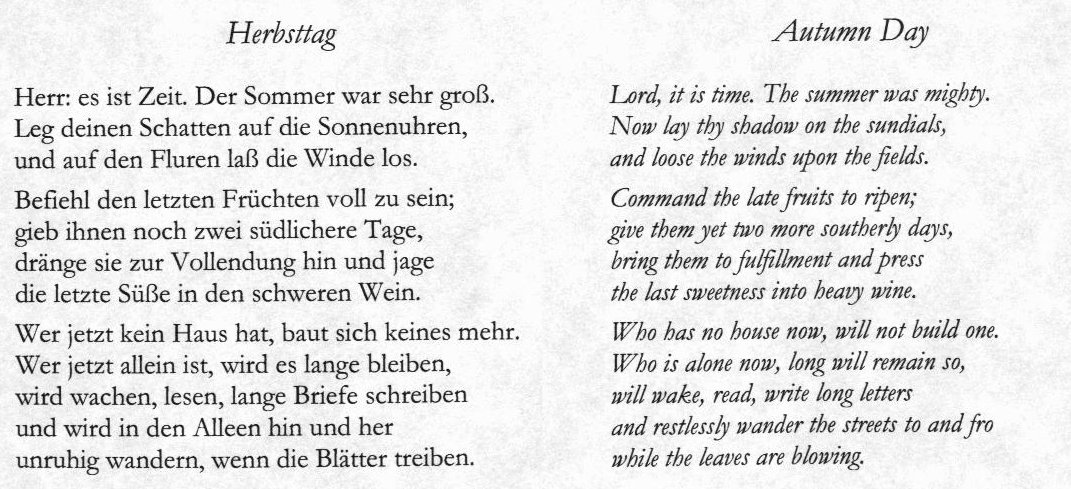

Herbsttag

STUDENT VOICES

Joe Smallhoover

So, one day in class, in response to a flippant comment (for once not from me), Frank smirked and said, “Of course you know why your parents pay the outrageous tuition here, don’t you. It’s so you can make brilliant conversation at cocktails parties when you’re out in the real world.”

So, one day in class, in response to a flippant comment (for once not from me), Frank smirked and said, “Of course you know why your parents pay the outrageous tuition here, don’t you. It’s so you can make brilliant conversation at cocktails parties when you’re out in the real world.”

My inner response was “Yes! at last someone who understands my life’s ambition.” And at that moment I knew we would be good friends for many years. Tja. What else can one say about one’s mentor and friend of 35 years? What can one say about a teacher who could glower down a seminar table at some miscreant student like Moses catching the Israelites worshipping the Golden Calf, and then moments later erupt into peels of window-shattering laughter? Frank and I came to Duke the same year. I was 17 and he … well he must have been 70 – or so he seemed to me: so perceptive, so penetrating, so … well … provocative. As I grew older he somehow got – at least for a while – younger. I’m not quite sure when the “Dr. Borchardt” became simply “Frank”, but it must have been while I was studying for my M.A. exams in German at UVA. He called me out of the blue and said “You’d better know the name of the dog in ‘Der Blonde Eckbert’, because it’s question number 3 on your exam” . Well he was wrong – and I called him back later to tell him so – it was question number 2. The answer by the way is Strohmian. Frank pushed me in so many ways to excess – oh – I meant to say success. No. Maybe excess was right after all. Nja. Once he turned to me in the middle of the conversation at German Table and said “If you’d been alive in the Middle Ages they’d have burned you for a witch. How did you learn such good German?” I told him that my first course at Duke had been with Dr. Phelps. (That was true). Years later in a café in Berlin, he suddenly interrupted a conversation and said “Your grammar really stinks. Where did you learn it?” I told him (and this was not true but he didn’t remember) “In your Baby-Deutsch course in 1971.” And then I laughed. Frank and I spoke often over the past 35 years. He always had time to listen and give me sound advice, even if it was sometimes put to me in challenging ways. His example in the classroom inspires my own teaching and his love of provocation is alive to a less perfected sense in me. I never shared his fondness for innovation and technology though. His was the first microwave oven I ever saw. He said it warmed up the coffee really well. I didn’t get the point. And so it was and has been. To quote Paul Fleming: “Die Zeit ist was / und nichts. Der Mensch im gleichem Falle. Doch was dasselbe was / und nichts sey / zweifeln Alle.” In fact, I’m not quite sure what that means, but it is from one of those damn poems he made us memorize and I have never forgotten it. But a quote I do understand is this one from Somerset Maugham: “If the rose at noon has lost the beauty it had at dawn, the beauty it had then was real. Nothing in the world is permanent, and we’re foolish when we ask for anything to last. But surely we’re still more foolish not to take delight in it while we have it.” So, I love a good cocktail party and think of Frank every time I’m telling a story at one, just as I do when I walk through Salzburg’s St. Peterhof cemetery or across the Alexander-Platz. Thank you Frank.

Executive Director, LeadGreen.org Trinity '78

I have that feeling now. Frank’s given me an assignment, which I haven’t yet finished. But with your help I will. When Paul and I were sitting with him at the Hospice, we asked him if he had any preferences for the funeral. Maybe something from Wagner, which he loved, or a reading from Faust? He shook his head. Wasn’t there anything he’d like us to read? Very quietly he said, “Something to make them debate.” “You want to stir up controversy?” I asked. “Something to make them debate,” he repeated, and smiled. So with your permission I’d like to engage in some Borchardtian rhetoric, which he dearly loved. I remember as a student being shocked at the intensity of his argument. I’d come from Washington state, where economics and politics were matters of principles. He’d come from the fiery history of Europe, where these things were matters of life and death. He would go to what seemed any length to eradicate them from my student mind. Sometimes it seemed even inappropriate lengths. Did anyone else here have any testy exchanges over politics with Frank? (A couple of the mourners raise their hands.) Will anyone share one? (One stands up and says, “The English Department is a Stalinist safe-house.” General hilarity.) Let’s try some other Borchardtisms. We’ll have a debate. I’ll be me and you’ll all be Frank. I’ll start. I say: You know, Frank, I’m an environmentalist. I don’t think it’s right that this generation uses resources and causes global warming that may be catastrophic for generations in the future. And you all say, (Henry reveals the first Borchardtism on a flipchart.) “What an excellent example of liberal apocalyptic myth-making.” That’s an interesting response, Frank. But we’re talking about putting at risk the futures of everyone who comes after us. And you all mutter under your breath, and keep right on muttering, no matter what I say, (Henry reveals the second Borchardtism on a flipchart.)“50 million people. 50 million people.” And as you all mutter – keep going – I make my usual argument, saying “We can afford to moderate our own consumption a little. It won’t effect our quality of … are you listening to me … all right, all right … you can stop muttering now. What 50 million people?” Who here knows what he meant by the 50 million people? (Peggy Abrams explains that Borchardt was referring to.) “The 50 million people who died in the Soviet Union under Stalin.” Of course that’s what he meant. But he would just roll his eyes and say, (Henry reveals the third Borchardtism on a flipchart and everyone says aloud.) “Yet another abyss, Mr. Straughan?” So by this time I would begin to heat up and I’d fling back, “You’re not doing much to foster civil democratic debate, are you.” To which he would answer, in his unique Borchardtian style, with a big belly laugh tinged with sarcasm, “Ha!” Everyone try it with me. “Ha!” Thank you all very much.

M.B.A. Candidate, University of Pennsylvanuia Wharton School/Lauder Institute Trinity '02

The first time I walked into Professor Borchardt’s German Drama class, I was completely intimidated. The all-black attire, shock white hair and beard, piercing blue eyes looking out sharply over rimmed glasses and booming voice were enough to make me want to bolt to the farthest corner of the room and curl up into a tight ball. I discovered very quickly, however, that his daunting presence masked a hearty laugh and one of the kindest and most caring souls I had ever met. His love for the subject and his zest for teaching transcended the classroom, and we frequently found ourselves in a series of fascinating, tangential conversations. Never before had I been sad to leave a classroom or so eager to come back two days later. As the Drama class neared its end, I looked forward to taking his Fairytales class, the real reason I had decided to major in German. Except there was one problem: it wasn’t being offered. Convinced there was some mistake, I asked Professor Borchardt, who confirmed the story. “Next year,” he told me cheerfully. But I thought, “No no no no no. There’s no next year – I’m graduating in May!”

The first time I walked into Professor Borchardt’s German Drama class, I was completely intimidated. The all-black attire, shock white hair and beard, piercing blue eyes looking out sharply over rimmed glasses and booming voice were enough to make me want to bolt to the farthest corner of the room and curl up into a tight ball. I discovered very quickly, however, that his daunting presence masked a hearty laugh and one of the kindest and most caring souls I had ever met. His love for the subject and his zest for teaching transcended the classroom, and we frequently found ourselves in a series of fascinating, tangential conversations. Never before had I been sad to leave a classroom or so eager to come back two days later. As the Drama class neared its end, I looked forward to taking his Fairytales class, the real reason I had decided to major in German. Except there was one problem: it wasn’t being offered. Convinced there was some mistake, I asked Professor Borchardt, who confirmed the story. “Next year,” he told me cheerfully. But I thought, “No no no no no. There’s no next year – I’m graduating in May!”

I talked to Krysta, my partner in crime, and we decided to ask him to teach it anyway. He was rather apologetic, but explained that his class schedule was already full and he wouldn’t have time. But I wasn’t giving up so easily. I persisted and pleaded, and he stood firm, so we ended up locked in a battle of wills – his will against mine. Finally, using a little theatrical melodrama I had learned from the master himself, I pulled my last card. “But Professor Borchardt,” I implored, “you have students dying to learn and we’re begging you to teach us. How can you say no? Isn’t this what you professors live for?” But it didn’t work. He just shook his head – and that was the end of the conversation. I left slowly, dejected by the outcome, but by the time I had trudged home, I had an email waiting for me. “You win,” was all he had to say.

I talked to Krysta, my partner in crime, and we decided to ask him to teach it anyway. He was rather apologetic, but explained that his class schedule was already full and he wouldn’t have time. But I wasn’t giving up so easily. I persisted and pleaded, and he stood firm, so we ended up locked in a battle of wills – his will against mine. Finally, using a little theatrical melodrama I had learned from the master himself, I pulled my last card. “But Professor Borchardt,” I implored, “you have students dying to learn and we’re begging you to teach us. How can you say no? Isn’t this what you professors live for?” But it didn’t work. He just shook his head – and that was the end of the conversation. I left slowly, dejected by the outcome, but by the time I had trudged home, I had an email waiting for me. “You win,” was all he had to say.

We developed our friendship over the course of the year, and Professor Borchardt was instrumental in helping me secure a fellowship in Germany. We kept in regular contact, and when I returned to the US and began working at the Democratic National Committee and the Kerry campaign, our friendly political banter kicked into high gear. At some point, he colorfully asked, “Are you enjoying the take-no-prisoners, scorched-earth, total war decreed by the DNC? Now, if they lose, will Terry [McAuliffe], at long last, be expected to fall on his sword?” Likewise, when I went to work in Wisconsin, a swing state, he merrily ranted, “If the [democrats] win, it will be _your_ fault! Are you ready to bear the guilt?” I told him I was. Every time I came back to Duke, we sat at brunch or dinner for hours, catching up, sparring politically and discussing travel to far-away places. I sent him notes from my consulting trips to Hungary, Bulgaria and Armenia, and in return, he gave me history and stories from when he was there. When I decided to apply to business schools last year, he graciously agreed to write recommendations for me while gleefully pointing out the “contradiction between the DNC and high capitalism.” Now enrolled in a dual-degree program, getting an MBA and a MA in International Studies focused on German language and culture, I have to reflect on how it all started. And I know, it goes back to Professor Borchardt. Without his influence, I would not be where I am today. I have him to thank for shaping my life.

Ph.D. Candidate, Neurorecognition Lab Department of Psychology, Tufts University Trinity '02

I could not say that I knew Frank Borchardt with any profundity; but I like to think he gave a clear idea of who he was in his teaching—and he was certainly not one of those people you forget. He made a distinct first impression; I once told my mother that he looked like a German Santa Claus in black instead of red, and she later recognized him unprompted, across the quad. I’m sure many of his former students would recognize his devilishly perfect imitation of a German accent, usually delivered with eyes darting in mock suspicion under his wild eyebrows; his habit of sitting back in his chair and rocking from side to side when he laughed, which was often; and his uniformly voracious habits of mind which linked so many disparate topics.

I could not say that I knew Frank Borchardt with any profundity; but I like to think he gave a clear idea of who he was in his teaching—and he was certainly not one of those people you forget. He made a distinct first impression; I once told my mother that he looked like a German Santa Claus in black instead of red, and she later recognized him unprompted, across the quad. I’m sure many of his former students would recognize his devilishly perfect imitation of a German accent, usually delivered with eyes darting in mock suspicion under his wild eyebrows; his habit of sitting back in his chair and rocking from side to side when he laughed, which was often; and his uniformly voracious habits of mind which linked so many disparate topics.

He was remarkably generous with his time; my senior year, a friend and I convinced him to teach a class on the Grimm Maerchen to the two of us, although it wouldn’t normally have been offered that year. Looking back, this class was one of the most striking examples in my undergraduate career of being treated as an adult intellect by a professor: that class will always stand in my memory as a halcyon of collegiality and good cheer. He was also strikingly a gentleman, as antiquated a term as that seems; his political views were very different from many of his students’, and although we knew this—and at the time probably could have given a decent summary of those views—he never used even the subtle and often unconscious tricks of instructor to diminish others’ opinions. His congeniality, generosity, and curiosity, as well as his kindness both professional and personal, are a standard I strive to meet myself, both personally and professionally. READINGS

Bonkers by Clara Yu and

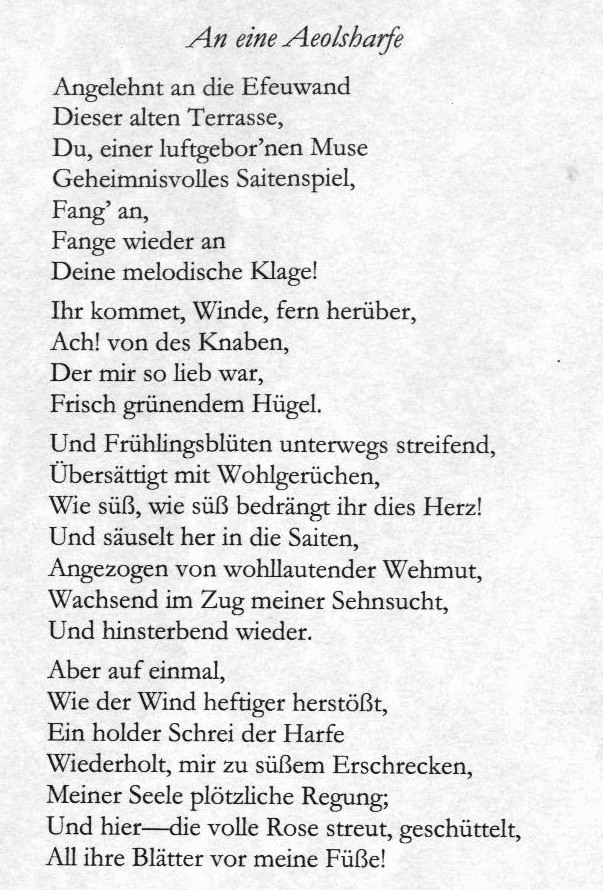

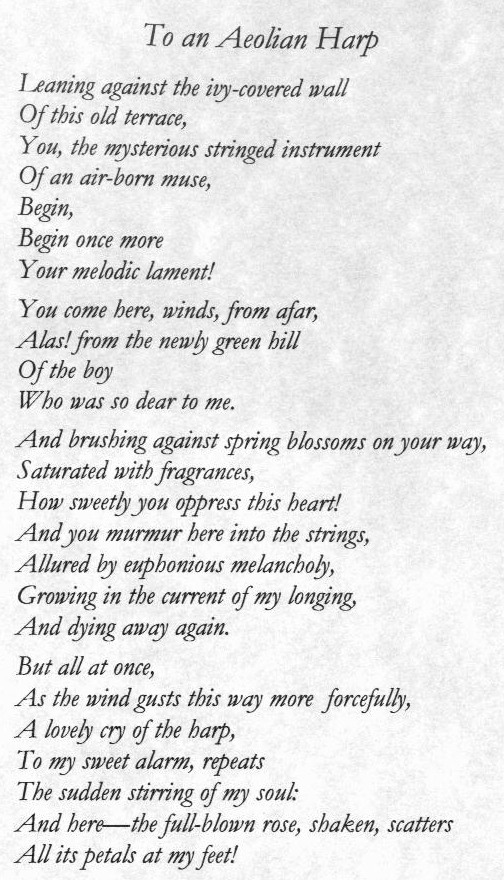

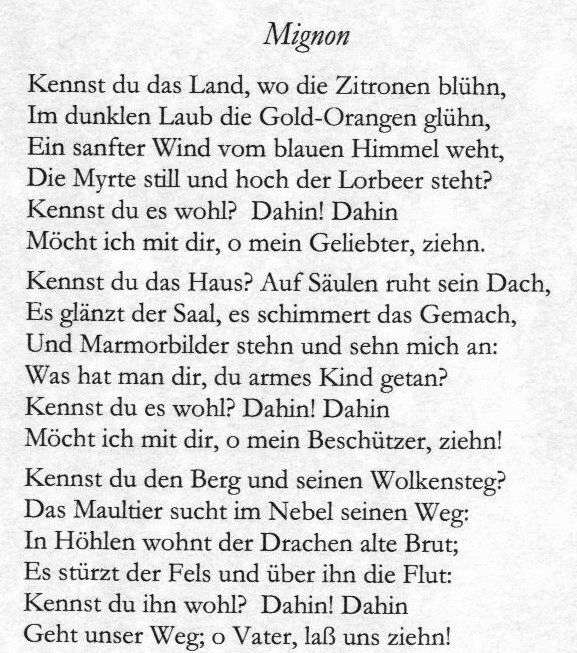

An eine Äolsharfe Musik

Susan Dunn, soprano

CLOSING

Duke has lost a Great Professor. Thank you Inge – Frank I am sure is enjoying this program. You have brought us together in a wonderful way. A University is only as good as its Faculty and Frank was the best. What a sense of humor. I never had a conversation with him that didn’t end in laughter. He loved his students, his field of literature, drama, and music, a great meal, his dogs, his friends, and he loved his University. What a rarity to find a Professor of German Languages receiving grants from the National Security Agency while teaching a College Course in Grimms’ Fairy Tales. And so we take inspiration from his Life – so well described today and so well lived. Let us rededicate our lives to the values he held dear – And go forth in the Joy of having known a great man.

POSTLUDE

Dell Williams, piano

|

I have some pictures and comments dealing with Frank’s early years that I would like to share with you.

I have some pictures and comments dealing with Frank’s early years that I would like to share with you.

Frank’s conservatism, was initially inherited from our father. This is Hermann Borchardt with Frank when he was between 1 and 2.

Hermann Borchardt, like many other German intellectuals in the 1920’s and early 1930’s had Marxist leanings but, for good reason made a complete reversal and became a vehement anti-communist.

Frank’s conservatism, was initially inherited from our father. This is Hermann Borchardt with Frank when he was between 1 and 2.

Hermann Borchardt, like many other German intellectuals in the 1920’s and early 1930’s had Marxist leanings but, for good reason made a complete reversal and became a vehement anti-communist.

Frank was born into poverty but was probably too young to be impacted by it. Our Dad was a hard worker, constantly writing but that didn’t put much bread on the table. We lived in a low rent neighborhood in Manhattan -- 102nd street between Amsterdam and Columbus avenues. To picture our neighborhood think of “West Side Story”. It could have been shot on our block. It was an Irish neighborhood during the Puerto Rican immigration with the culture clash that Leonard Bernstein portrays.

Frank was born into poverty but was probably too young to be impacted by it. Our Dad was a hard worker, constantly writing but that didn’t put much bread on the table. We lived in a low rent neighborhood in Manhattan -- 102nd street between Amsterdam and Columbus avenues. To picture our neighborhood think of “West Side Story”. It could have been shot on our block. It was an Irish neighborhood during the Puerto Rican immigration with the culture clash that Leonard Bernstein portrays.

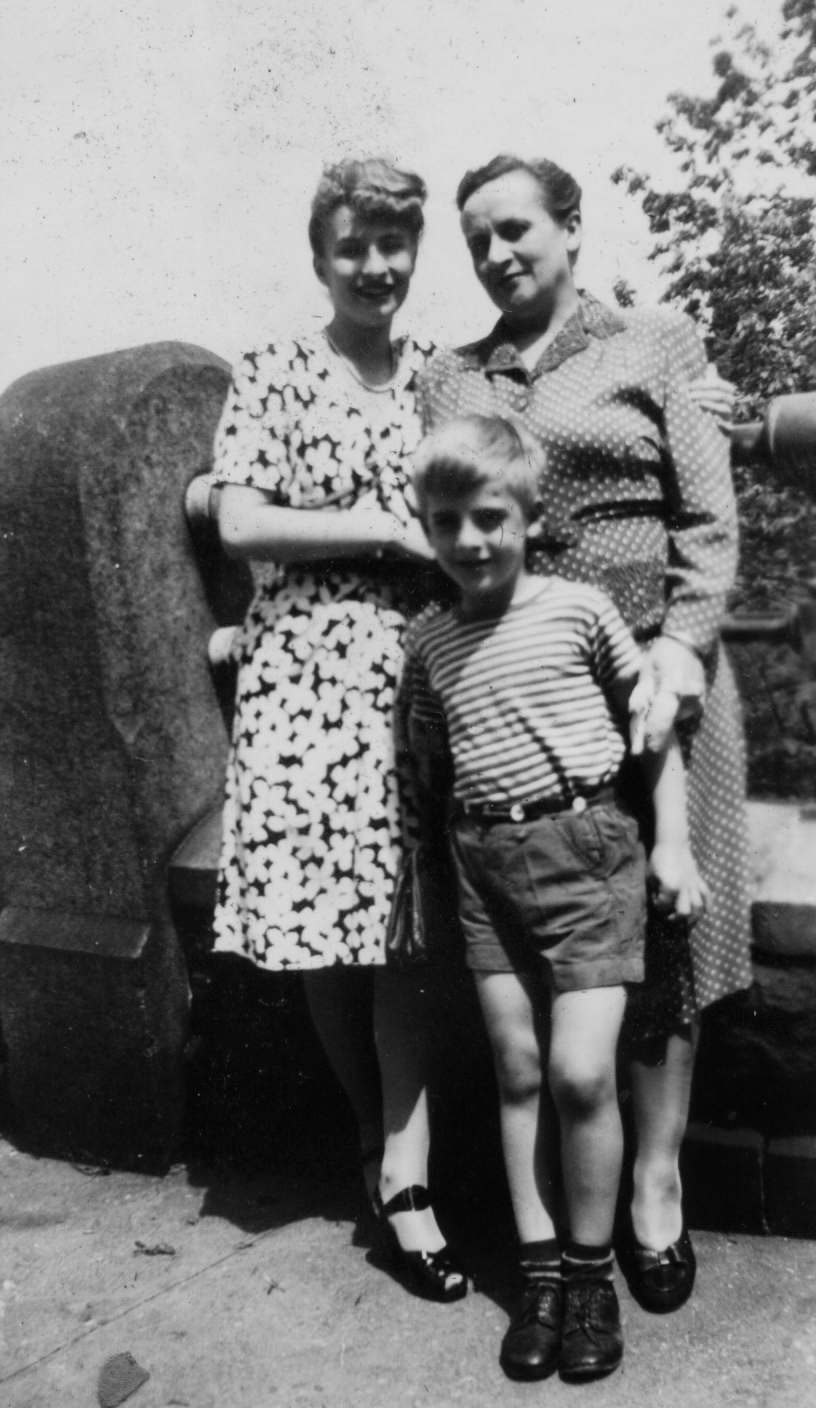

When our older sister Sue became old enough to work and contribute to the family income we moved to a better neighborhood; into an apartment overlooking Morningside Park, which begins at 110th street and runs to 123d street. Morningside park is a hillside with Morningside heights to the west – where Columbia University is located --and a portion of Harlem to the east. The picture is of Frank with sister Sue & Mimi on Morningside drive.

When our older sister Sue became old enough to work and contribute to the family income we moved to a better neighborhood; into an apartment overlooking Morningside Park, which begins at 110th street and runs to 123d street. Morningside park is a hillside with Morningside heights to the west – where Columbia University is located --and a portion of Harlem to the east. The picture is of Frank with sister Sue & Mimi on Morningside drive.

He was as unique in personality as in appearance; at first I was taken aback by the many facets of his knowledge: the history of user interface design, Chinese history, the development of languages, cognitive science; all figured into his interests—and his classes. Although they weren’t always the most focused of classes, they were never dull; in intermediate language classes, where some instructors come off as bored and boring, he was explosive and captivating. In higher-level classes, he gave full reign to his tendency for storytelling and embellishment, and discussions became far-ranging, ambitious, and spirited.

He was as unique in personality as in appearance; at first I was taken aback by the many facets of his knowledge: the history of user interface design, Chinese history, the development of languages, cognitive science; all figured into his interests—and his classes. Although they weren’t always the most focused of classes, they were never dull; in intermediate language classes, where some instructors come off as bored and boring, he was explosive and captivating. In higher-level classes, he gave full reign to his tendency for storytelling and embellishment, and discussions became far-ranging, ambitious, and spirited.